Richard Mayhew, known for his hazy abstract paintings that sometimes resembled landscapes, died on Thursday at the age of 100.

Throughout his life, Mayhew was often recognized as a landscape painter, but he avoided that title, correcting people by telling them that he was, in fact, a landscape painter. appearance mind a painter. “Because when I go to a canvas, I’m just putting paint on it and it’s understated, it’s highly suggestive,” he explained in a 2019 oral history as part of the Getty Research Institute’s African American Art History Project. “Since I am involved with the feeling of desire, ambition, love, hate, fear – those are my paintings. It takes on that kind of structure and imagery.”

He added, “I use landscape as a metaphor to express feelings. That’s it.”

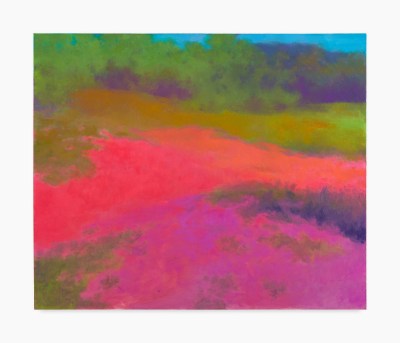

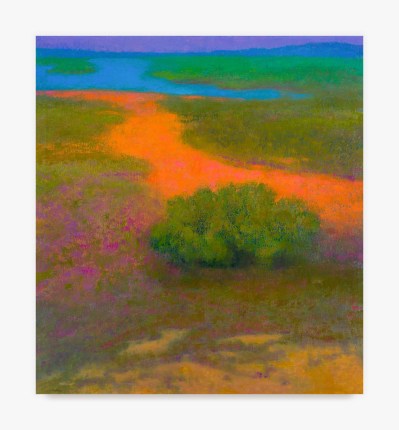

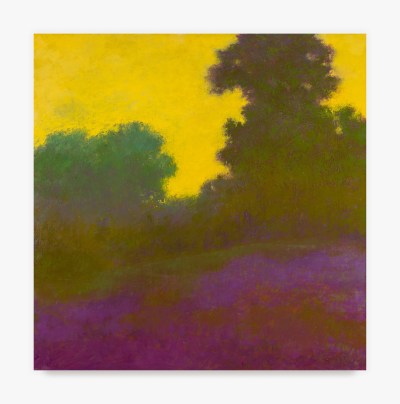

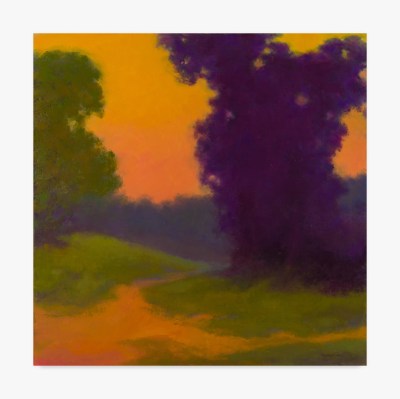

Mayhew’s mind paintings have an ethereal quality, in which different colors blend together. Sometimes, they are electric shocks of violet, magenta, neon green, pink, and goldenrod, similar to color photo negatives. In other canvases, they are more dangerous tones of the same shade that blow into each other. Bodies of water and forests of trees and shrubs arise from several canvases; others are completely abstract, perhaps suggesting a horizon or a crashing wave.

In an interview with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, he recalled visiting a former plantation in Georgia. He noticed a large barren area on some of the lands and asked himself what happened in that area and how the enslaved people who worked on the plantation were treated. “So I made a picture of that area, just based on feeling. I wanted to engage in an emotional interpretation,” he said. He would often say that he was “painting forty acres and a mule,” a reference to the promises made to formerly enslaved people after the Civil War that were never fulfilled.

He added, “There is a certain mystery in the shadow beneath a bush. This small range of emotions is representative of almost all possibilities.”

Richard Mayhew, Aura Pamela2004.

Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Venus Over Manhattan.

As part of a tribute to Mayhew’s centenary celebrations published by Type of CultureArtist Lisa Corrine Davis, who met Mayhew in 2018, said, “Richard paints believable but non-existent landscapes that speak to identity through ideas of space as a way of understanding the world. It recognizes that space is closely related to the Black experience—spaces we can be, spaces we are left with, and spaces that have been taken away from us. Richard’s landscapes are not observed and preserved, but built and designed, one mark at a time, that only exists in his mind’s eye.”

However, Mayhew is best known for his association with Spiral, a group of African American artists who formed in 1963 at the height of the civil rights movement and disbanded after their one group show in 1965. The group consisted of 14 men, ie among them Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, Hale Woodruff, and Charles Alston, and one woman, Emma Amos; Felrath Hines invited him in after seeing his work. The motivation behind the formation of Bíseach was that the artists could discuss issues that directly affected Black artists. Mayhew was the last surviving member of the group and the only one not to take part in a panel discussion in 1966, published in ARTnewsabout the group.

“It was a think tank [of] all African American artists,” he said in the SFMOMA interview. “He was involved in debating and challenging the system and also challenging each other. … we took on the challenge of the community in New York at the time, which did not include African-American artists in the various major exhibitions and galleries. And Spiral was part of the promoters of this time to challenge the arts system.”

Richard Mayhew, Over the Bramble Bush1996–97.

Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Venus Over Manhattan

Richard Mayhew was born in 1924 and raised in Amityville, New York. The artist community out on Long Island was an inspiration for young Mayhew who began drawing and painting at a young age, with a local artist acting as his art teacher starting when he was 14. During his youth, he was a frequent visitor . to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, studying the works of European and American masters in the institution’s collection.

In the GRI oral history, Mayhew said his ancestry was a mix of African American and Native American, including Shinnecock and Cherokee-Lumbee, but he often did not identify as the latter for much of his life “because on every occasion I mentioned. [being Native American]he was rejected. So I lived my life as an African American,” he said.

Later in life, Mayhew would say that his desire to paint within a landscape mode came from both parts of his ancestry. “That combination is why I paint landscape as nature, I guess,” he said in the SFMOMA interview. “In terms of African Americans and Native Americans, their blood is in the soil of the United States.”

Richard Mayhew, Rituals2005.

Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Venus Over Manhattan

Mayhew served in the Marines during World War II and was eventually awarded the Congressional Special Medal. (His first wife, Dorothy Zuccarini, who died in 2015, “was the one who discovered and pursued Rick’s right to donate the medal”, according to an introduction to the oral history by their daughter, Ina Mayhew .)

After his service, he spent time in Europe, visiting various museums on the continent, with stops in Paris, Amsterdam, and Germany. He moved to New York when he returned to the USA in 1947, aged 23. Around this time, he began his formal education in art history and art making, taking courses at Columbia University, the Brooklyn Museum School of Art, and the Pratt Institute, as well as the Art Students League, although he was not enrolled. officially there. Among his teachers during this era were the American painters Edwin Dickinson and Reuben Tam. Mayhew had his first solo show at the Brooklyn Museum in 1955.

Mayhew would continue his studies in Europe in the late 50s and early 60s, by winning the John Hay Whitney Fellowship in 1959, which financed a year of study at the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Florence, and then receiving a grant from the Institute. Ford Foundation, which allowed him to stay in Europe, where he also studied at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Mayhew also began teaching early in his career, which would become a lifelong commitment. He taught at the Brooklyn Museum School of Art and the Art Students League, where he studied, as well as at Smith College and Pennsylvania State University. He taught at Penn State for 14 years, retiring in 1991 as professor emeritus.

Richard Mayhew, Crescent2008.

Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Venus Over Manhattan

When Mayhew moved to New York, Abstract Expressionism was on the rise and he hung out at the Cedar Bar, an Ab-Ex watering hole, with many of the artists before they became famous. Although his artistic method certainly included some elements of movement, Mayhew did not fully embrace the totality of abstraction. (A more important influence on him was George Innes, a 19th century Tonalist painter.)

“It reached a point where everything ends,” he said of Abstract Expressionism in the GRI’s oral history. “Everything is finished, and you don’t go back to start from nothing. What do you have but nothing? Symptomatic of what is going on in the world right now. It is a symptom of destruction and how to avoid that and find a norm, so that the norm is in the past.”

Like many Black artists of his generation, Mayhew had an uneven relationship with the mainstream art world. For example, the artist has only one work at the Whitney Museum, a painting from 1960 that he acquired in 1962. Despite receiving grants to study in Europe, being inducted into the National Academy of Art in 1969, and being part of de Spiral, has not been canonized in many accounts of postwar American art history.

Richard Mayhew, Untitled, n.d

Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Venus Over Manhattan

His work has only recently been re-evaluated and accepted. The first monograph of his work was only published in 2020. The last time he had a retrospective was in 2009 which was spread across three venues in the Bay Area: Museum de Saisset, Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD), and the Museum of Art & History in Santa Cruz. (He had moved to the Santa Cruz area from the East Coast by this point.) In 2020, SFMOMA dedicated a gallery to his paintings, six of which were donated by Pamela Joyner, a ARTnews Top 200 Collectors and SFMOMA trustees who have long supported his work. He was the subject of a 40-painting survey at the Sonoma Valley Art Museum in California last fall.

“Richard Mayhew’s legacy is not only his mastery of color and landscape but his ability to transcend the physical world, expressing emotion and cultural memory,” Galleries ACA president Dorian Bergen said in a statement. (Mayhew is a former representative of ACA Galleries. The artist’s work is currently shown at the Venus Over Manhattan gallery.) enriches our sense of identity and place. He will be very welcome.”

But color became a central focus of Mayhew’s practice, which he continued well into his 100th year. Venus Over Manhattan will open a show focusing on Mayhew’s watercolours, spanning the past thirty years including new work, on November 7 in New York. His bold use of color can often be discombobulating, even searing your retinas. The colors vibrate in ways that are hard to put into words. Over the past eight years, he had mastered how to manipulate the eye with his use of color, he said. “Color was a very sensitive part of my development,” he told SFMOMA. “How it affects one’s emotions. I think you can’t look at a picture and see one thing. This other element is going on through the use of color and how the eye is captured in the after image.”

He added, “What does love look like? What color is it? What does fear look like? What color is fear? All my paintings are based on emotion.”

#Richard #Mayhew #Abstract #Artist #Painted #Grim #Visions #World #Dies